Understanding Kidney Disease: Stages, Causes, Symptoms, Treatments & Prevention

By: Michael Aragon, MD

Chief Medical Officer

Summary

Kidney disease is a complex, progressive and under-recognized public health problem. In the U.S., chronic disease treatment options are becoming more patient-focused, with an increased use of home dialysis.

The kidneys are responsible for incredibly vital functions in the body, including filtering all of the body’s blood every 30 minutes, removing toxins, regulating blood pressure, sending the signal to make red blood cells, keeping the bones strong and maintaining water balance. Diseases affecting these organs can be life-threatening. Chronic kidney disease, which can progress through the early stages without any symptoms, is the ninth leading cause of death in the U.S. and a serious and growing public health problem 1. Today, more than 37 million Americans are living with chronic kidney disease (CKD), and more than 810,000 have end-stage kidney disease (ESKD; also known as end-stage renal disease, or ESRD), meaning they need dialysis or a kidney transplant to stay alive. Currently, more than 100,000 Americans newly begin dialysis each year to treat ESKD 2. Multiple pre-existing conditions and demographic factors such as diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, family history and an aging population are expected to drive the U.S. prevalence of kidney failure to one million individuals by 2030, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

Kidney disease, also referred to as kidney failure, can be temporary or permanent and typically occurs due to an underlying medical condition. In acute kidney injury (AKI), the injury is usually temporary, even if the patient needs dialysis for some time, and most often occurs as a complication of a short-term serious illness, such as COVID-19. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is typically due to a long-term condition like diabetes or high blood pressure, and gradually worsens over time, potentially resulting in ESKD. Outset Medical estimates that approximately 40% of the 125,000 newly diagnosed ESKD patients in the U.S. each year begin their dialysis journey in a chronic setting, either at home or in an outpatient dialysis clinic, while about 60% “crash” into dialysis in the hospital, with no clinical care in advance. CKD is associated with increased hospitalization, productivity loss, morbidity and early mortality.

Here, we overview the types and stages of kidney disease, the causes, symptoms, treatments and prevention. It is important to understand the risks of kidney disease, and if at high risk, to see a kidney doctor (nephrologist) to diagnose it and learn how to stop or slow its progression early.

Types and Tests

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI; also referred to as acute renal failure, or ARF) can be caused by sudden illness (including being a severe complication of COVID-19), injury or toxins. It is frequently reversible, and its rapid onset leads to short-term symptoms. It is typically treated in a hospital acute unit and/or bedside in the ICU.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD, also referred to as chronic renal failure, or CRF) can be caused by a number of risk factors and conditions. It is generally irreversible, and kidney function slowly gets worse over time. When discovered very late, it typically requires treatment in a hospital acute unit and/or bedside in the ICU, and on a chronic basis it is treated in a dialysis clinic, long-term acute care facility (LTAC), skilled nursing facility (SNF) or at home.

Anyone can get kidney disease at any time, and most people with early disease do not have symptoms. That is why it is important to have a kidney function test, and to know these numbers.

Kidney function is determined using two tests: ACR (Albumin to Creatinine Ratio) and GFR. ACR is a urine test to see how much albumin (a type of protein) is in the urine. Having protein in the urine may mean that the kidney’s filters, known as glomeruli, have been damaged. This is a sign of early kidney disease. If a urine test comes back positive for protein, the test should be repeated to confirm the results, according to the National Kidney Foundation (NKF).

GFR levels, as outlined by disease stage below, are the best overall index of kidney function. First, the blood is tested for a waste product called creatinine, that comes from normal muscle wear and tear. Creatinine levels vary depending on age, sex and body size, and normally decline with age. As kidney disease progresses, the level of creatinine in the blood rises: levels of 3.0 and above in adults may indicate severe kidney damage (sources: NKF, eMedicineHealth, Loyola University Chicago). Testing for creatinine is then followed by calculation of the GFR level. NKF recommends using the CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation (2021) to estimate GFR. Either of the following must be present for ≥3 months to be defined as CKD, according to NKF:

• GFR less than 60

• ACR ≥30 mg/g or other markers of kidney damage

Kidney Disease Stages

There are five stages of kidney disease, based on how well the kidneys are able to filter out waste and extra fluid from the blood. The stages range from very mild (stage 1) to end stage (stage 5), as detailed below. Importantly, the earlier kidney disease is detected, the better the chance of slowing or stopping its progression.

• Stage 1: Normal or high GFR (GFR > 90 mL/min) – the kidneys are working well.

• Stage 2: Mild CKD (GFR = 60-89 mL/min) – the kidneys are working well, but there are signs of mild kidney damage.

• Stage 3: Moderate CKD (GFR = 30-59 mL/min) – the kidneys are working well enough to clean the blood but there is some damage to the kidneys that is likely to progress. This stage is separated into 2 sub-stages:

• Stage 3A: Moderate CKD (GFR = 45-59 mL/min) – the first stage that is identifiable by blood test alone; a patient is monitored more closely and underlying conditions that can affect progression are treated if applicable (e.g., blood pressure, urine protein).

• Stage 3B: Moderate CKD (GFR = 30-44 mL/min) – there is moderate damage to the kidneys. Continued treatment of underlying risk factors that worsen function (e.g., blood pressure, urine protein). A person still feels well and may still have no or minimal symptoms. At this stage, a person is more likely to develop complications such as anemia (a shortage of red blood cells) and/or early bone disease.

• Stage 4: Severe CKD (GFR = 15-29 mL/min) – there is evidence of poor kidney function and severe damage to the kidneys. A person likely has begun to feel some symptoms of kidney disease (e.g., swelling, fatigue, higher blood pressure). Continued treatment of underlying risk factors. Patient should be educated regarding transplant options and referral as well as dialysis options.

• Stage 5: End-Stage CKD (GFR <15 mL/min) – the kidneys are very close to failing or have failed. A person likely has significant symptoms (e.g., shortness of breath, significant swelling, worsening fatigue, loss of appetite). Patient needs a kidney transplant or may need to start kidney dialysis to sustain life.

(Sources: Outset Medical; Cleveland Clinic)

Risk Factors

Factors that can increase the risk of CKD include:

• Diabetes

• High blood pressure

• Heart (cardiovascular) disease

• Smoking

• Obesity

• Being Black, Native American or Asian American

• Family history of kidney disease

• Abnormal kidney structure

• Older age

• Frequent use of medications that can damage the kidneys

If a person is at risk for kidney disease, it’s important that they get tested annually.

(Source: The Mayo Clinic)

Causes

Other contributors and conditions that can cause CKD include:

• Glomerulonephritis: inflammation of the kidney’s filtering units (glomeruli)

• Interstitial nephritis: inflammation of the kidney’s tubules and surrounding structures

• Polycystic kidney disease or other inherited kidney diseases

• Prolonged obstruction of the urinary tract, from conditions such as enlarged prostate, kidney stones and some cancers

• Recurrent kidney infection, also called pyelonephritis

• Vesicoureteral reflux: a condition that causes urine to back up into the kidneys

(Source: The Mayo Clinic)

Signs and Symptoms

Signs of kidney disease develop over time if kidney damage progresses slowly. Loss of kidney function can cause a buildup of fluid or body waste or electrolyte problems. Depending on how severe it is, loss of kidney function can cause the following symptoms:

• Nausea

• Vomiting

• Loss of appetite

• Fatigue and weakness

• Sleep problems

• Urinating more or less

• Decreased mental sharpness

• Muscle cramps

• Swelling of feet and ankles

• Dry, itchy skin

• High blood pressure (hypertension) that’s difficult to control

• Shortness of breath, if fluid builds up in the lungs

• Chest pain, if fluid builds up around the lining of the heart

The signs and symptoms of kidney disease are often nonspecific, meaning that they can also be caused by other illnesses. Because the kidneys are able to make up for lost function, a person might not develop kidney disease symptoms until irreversible damage has occurred.

(Source: Mayo Clinic)

Treatments

Treatments for stages 1 and 2 kidney disease include eating a kidney-friendly diet, maintaining a healthy blood pressure, exercising, stopping smoking and keeping blood sugar under control. For stage 3 kidney disease, medications to treat illnesses that may have developed as a result of CKD and regular exercise can be beneficial. Those with stage 4 kidney disease will likely need a transplant or kidney dialysis in the near future to prolong their life, and once a person reaches ESKD, kidney dialysis or kidney transplant may be necessary in order to sustain life.

There are three main types of kidney dialysis: in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis (PD). It is important to note that dialysis is not a “one-size-fits-all” treatment. Acute renal failure patients can require dialysis for a short time until the kidneys recover, while chronic renal failure patients require permanent dialysis or kidney transplantation.

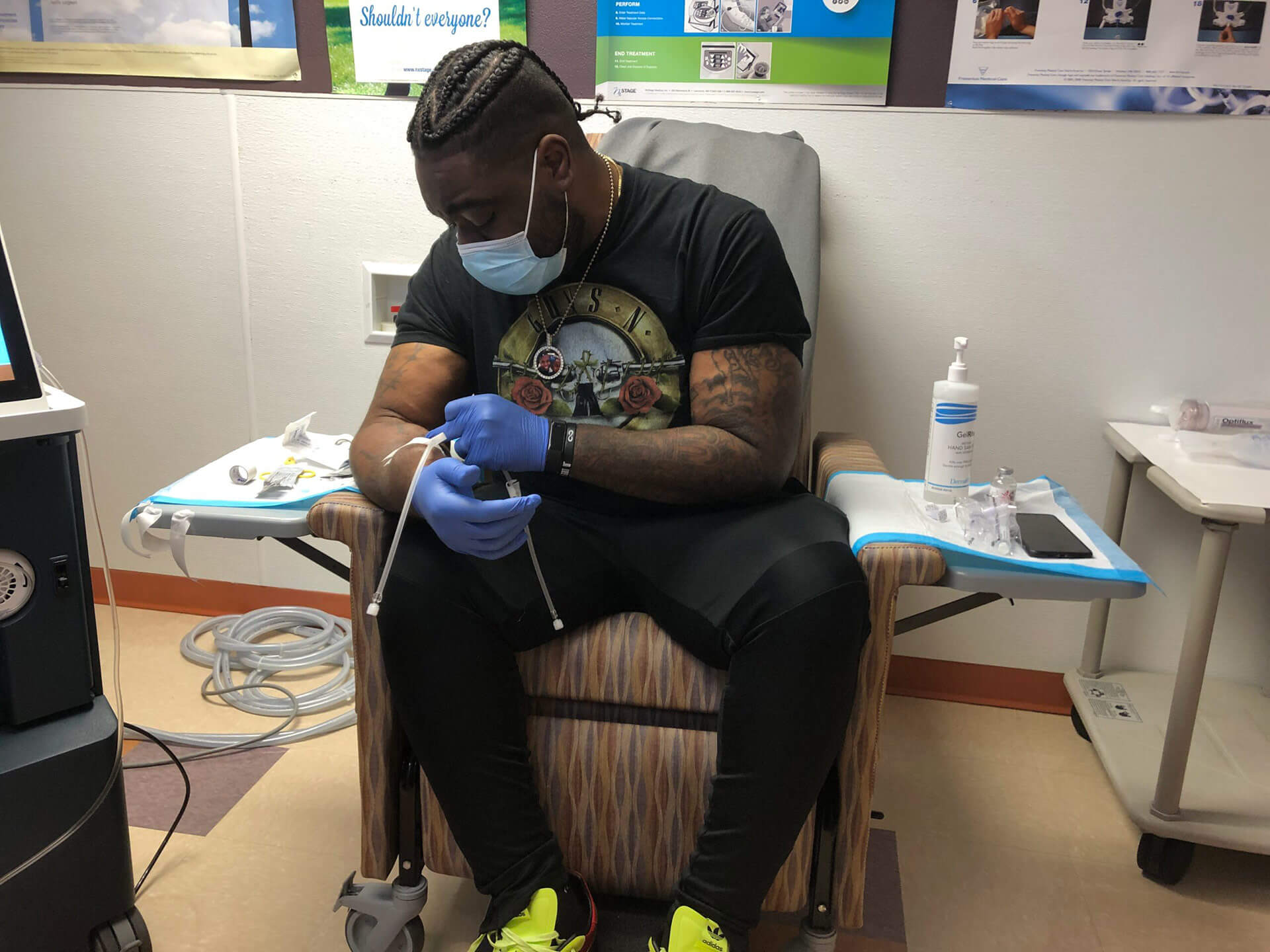

Kidney failure is most commonly managed with hemodialysis, a procedure by which waste products and excess fluid are directly removed from a patient’s blood through a vascular access using an external dialysis machine, such as the first-of-its-kind Tablo Hemodialysis System, as described below. During hemodialysis, the dialysis machine pumps blood through an external filter, called a dialyzer, that cleans the blood and removes excess fluid before returning the blood to the patient. During the process, the dialysis machine monitors blood pressure and other parameters, and controls how quickly blood flows through the filter and how quickly fluid is removed from the body.

Hemodialysis can be performed in multiple care settings, including the patient’s home, the hospital, outpatient dialysis center or in-center self-care dialysis. Although the majority of CKD patients today are treated in outpatient facilities, this long-unchanged standard is now shifting to become more patient-focused. An increasing number of patients annually are opting to care for themselves at home. Every patient has the option of dialyzing themselves at home, regardless of their personal situation. Many experts agree that home dialysis is the best option for treating kidney failure whenever possible, as it can mean greater scheduling flexibility, fewer food restrictions and better outcomes. Studies have shown that with self-care or home dialysis, many patients actually do better, including fewer hospital visits3, better quality of life4, longer life expectancy5 and the ability to maintain employment6. Recent factors including the COVID-19 pandemic, government initiatives and reimbursement changes* are also supporting a long-anticipated shift toward home hemodialysis.

* For the first time ever, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recognized a device (Tablo) as a substantial clinical improvement over other existing home hemodialysis technology and is incentivizing its use with an increase in payment to dialysis providers, known as the Transitional Add-on Payment Adjustment for New and Innovative Equipment and Supplies [TPNIES].

In PD, which is done daily, tiny blood vessels inside the abdominal lining (peritoneum) filter blood through the aid of a dialysis solution, following the surgical placement of an abdominal catheter. This sterile solution is a type of cleansing liquid that contains water, salt and other additives that draw the body’s toxins and excess water out of the blood and into the abdomen to later be drained out of the body.

There are two types of PD: continuous and automated. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) is machine-free and done while a person goes about their normal activities such as work or school. The treatment is performed by placing about two liters of cleansing fluid (commonly referred to as dialysate) into the abdomen and letting it sit, or dwell, for several hours before draining and refilling it. The filling is done by hooking up a plastic bag of cleansing fluid to the tube in the abdomen, and then raising the plastic bag to shoulder level so that gravity pulls the fluid into the abdomen. When complete, the plastic bag is removed and thrown away. After the fluid dwells for several hours, draining is done by connecting an empty sterile plastic bag to the tube and placing it below the abdomen or on the floor. Gravity will force the fluid out of the body and into the bag. Once empty, the filling process starts again so fresh dialysate can be placed into the abdomen and dialysis can continue. This process is usually done three to five times in a 24-hour period. With automated peritoneal dialysis, instead of relying on manual connections and gravity, a machine called a cycler pumps the fluid in and out of the body 3-5 times over 8-10 hours, usually during sleep. Peritonitis (infection of the abdomen) is an occasional complication of PD, although it should be infrequent with appropriate precautions.

Patients with ESKD can choose to switch dialysis methods at any time, and shouldn’t feel “locked in” to any one method. There may be medical, health, personal or lifestyle reasons why a certain type of dialysis is preferred over another. Patients should be sure to learn as much as they can about each type, and talk to their physician or nurse about which is best for them and their loved ones’ situation, lifestyle and preferences. Read more about the pros and cons of each dialysis method here.

Vascular Access: The Dialysis Lifeline

Depending on which dialysis treatment options are chosen, procedures are necessary to provide for regular access to the abdominal cavity or bloodstream.

There are four types of dialysis access:

• Arteriovenous (AV) Fistula: Used in hemodialysis, an access is made by surgically joining an artery and vein in the arm.

• Graft: Used in hemodialysis, an access is made by using a piece of soft tube to join an artery and vein in the arm.

• Bloodstream Catheter: Used in hemodialysis, a soft tube is placed in a large vein, usually in the neck.

• Abdominal Catheter: Only used in peritoneal dialysis, a soft tube is placed in the abdominal cavity.

An AV fistula is generally considered the first choice for most patients on hemodialysis because it generally lasts longer and has fewer problems such as infections and clotting. A fistula is a surgically created, permanent access located under the skin, making a direct connection between a vein and an artery. It is typically created in the non-dominant arm, in the forearm area. If the veins in the arm are not large or healthy enough to support a fistula, it may be created in the leg. The surgical procedure to create a fistula can be performed on an outpatient basis. It is important for the fistula to be placed ahead of time and completely heal and mature (enlarge and thicken) so it is ready to use when dialysis treatment begins. Depending on the person, it can take several weeks to several months for an AV fistula to heal and mature. Occasionally a fistula will fail to mature after a single surgery and may require an additional procedure to help maturation.

A graft is generally considered the second choice for vascular access for hemodialysis. Similar to a fistula, receiving a graft is a surgical procedure, but unlike a fistula, a synthetic soft tube is used to connect the vein to the artery. Grafts generally do not require as long to mature but may be more prone to complications of infection or clotting. Catheters are used as a temporary access when urgent dialysis is needed, but can also be placed for long-term use. While generally considered to be at highest risk for infection, many patients have used catheters for extended periods of time at home and in center. Some patients may switch from a catheter to a graft or fistula, or vice versa, depending on their particular situation.

If the access is a fistula or graft, a patient or their care partner at home, or a nurse or technician at a facility, will place two needles into the access at the beginning of each treatment. One needle carries blood from the body to the dialyzer. The other carries filtered blood back to the body. To tell the needles apart, the line connected to the needle that carries blood away from the body is red and is called the arterial line or needle. The line connected to the needle that carries blood back to the body is blue and is called the venous line or needle. These needles are connected to soft tubes that go to the dialysis machine. Blood goes to the machine through one of the tubes, gets cleaned in the dialyzer, and returns to the body through the other. If catheter access is used, it can be connected directly to the dialysis tubes without the use of needles. The catheter connectors are also color-coded red and blue to guide proper connection.

For peritoneal dialysis, a catheter needs to be surgically inserted into the abdominal cavity and attached to the abdominal wall. After a recovery period of two to four weeks, PD can be started.

Whether an access is a fistula, graft or catheter, it should be well taken care of, including keeping it clean to avoid infection and working well so that dialysis can be as effective as possible. A patient’s dialysis care team will teach them the steps of good dialysis access care.

(Source: National Kidney Foundation)

Prevention

You can protect your kidneys by preventing or managing health conditions that cause kidney damage, such as diabetes, high blood pressure and heart disease. The steps described below may help keep your whole body healthy, including your kidneys.

Food for Kidney Health

In earlier stages of kidney disease, choose foods that are healthy for your heart and your entire body: fresh fruits, fresh or frozen vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat or fat-free dairy products. Eat healthy, low sodium meals, and cut back on added sugars. A healthy diet should include no more than 2300 mg of sodium per day, according to NKF. As kidney disease progresses, your doctor may recommend that you limit foods high in phosphorus and potassium, as well as fluids. Patients should talk to a renal dietitian (someone who is an expert in diet and nutrition for people with kidney disease) to find a meal plan that works for them based on their food preferences and stage of kidney disease.

Make Physical Activity Part of Your Routine

At any stage of kidney disease, being active can help reduce symptoms, lower blood pressure and improve overall health. Try to be active for 30 minutes or more on most days. Patients should ask their healthcare provider about the types and amounts of physical activity that are right for them.

Aim for a Healthy Weight

The NIH Body Weight Planner is an online tool to help patients tailor their calorie and physical activity plans to achieve and stay at a healthy weight. If a patient is overweight or obese, they should work with their healthcare provider or dietitian to create a realistic weight-loss plan that includes types of food, calorie goals and a plan for increasing activity.

Other important steps to preventing kidney disease include getting enough sleep, stopping smoking, limiting alcohol intake and learning to better manage stress. Also, it is recommended that patients ask their health provider questions about kidney disease and how it applies to them and their health. The sooner a person knows that they have kidney disease, the sooner they can get treatment to help protect the kidneys from further damage.

Key questions to ask a healthcare provider:

• What is a normal GFR, and what is my rate?

• What is my urine albumin result?

• What is my blood pressure?

• What should I do if I have prehypertension?

• What is my blood glucose? (for people with diabetes)

• How often should I get my kidneys checked?

Other important questions:

• What should I do to keep my kidneys healthy?

• Do I need to be taking different medicines?

• Should I be more physically active?

• What kind of physical activity can I do?

• What should I eat as part of a renal diet?

• Should I be on a low potassium diet?

• Am I at a healthy weight?

• Do I need to talk with a dietitian to get help with meal planning?

• Should I be taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs for my kidneys?

• What happens if I have kidney disease?

Source: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health

Tablo Hemodialysis System Disclaimer: Results may vary. Keep in mind that all treatment and outcome results are specific to the individual patient. Please consult your physician for a complete list of indications, warnings, precautions, adverse events, clinical results, and other important medical information. It is important that you discuss the potential risks, complications, and benefits of this product with your doctor prior to receiving treatment, and that you rely on your physician’s judgment. Only your doctor can determine whether you are a suitable candidate for this treatment.

References:

CDC Chronic Kidney Disease Basics

CDC, Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2021

In-center self-care hemodialysis: An unappreciated modality in renal care. (Jones ER, James LR, “Neph News and Issues” 2011; 9:31-33,37)

Quantity of Dialysis: Quality of Life—What is the Relationship? (Morton AR, Meers C, Singer, MA, et al., J of Am Society of Artificial Internal Organs, 1996; 42 (5): M713-M717, 1996)

Survival in Daily Home Hemodialysis and Matched Thrice-Weekly In-Center Hemodialysis Patients (Weinhandl EDLJ, et al. “J Am Soc Nephrol.” 2012;23:895–904)

A Discrete Choice Study of Patient Preferences for Dialysis Modalities (Walker RC, et al. “Clin J Am Soc Nephrol.” 2018; 13: 100–108)